WWII Memoirs: Part 4 – Koblenz

by Richard Manchester | 27 Sep 2008

I was a member of K Company – 345th Regiment. I was in the Communications Section of Company Headquarters, carrying the SCR536 Handy Talky, relaying and receiving messages to and from the platoon leaders or carrying the SCR300, communicating with Battalion Headquarters. What follows are my experiences during this time. It may be totally different from the experiences of other surviving members of my company. You are generally only aware of what is happening in a radius of 100 feet or so. Some incidents I can remember as part of a chain of events. Other incidents are isolated and I can’t put them in context. I will try to contribute more as time and memory permit.

KOBLENZ

The enduring cold was gradually coming to an end. It was mid-March. The worst of it had been cold feet. They were numbingly cold all the time unless we could capture a village, occupy houses and build fires. If your feet were wet and cold, it was worse. Trench foot with blackened toes could send you back possibly with gangrene and amputation. We were issued shoe-pacs with rubber bottoms, too late to be effective. At least it reduced the incidence of trench foot. We had wool knit gloves. They were usually wet, with the wetness of snow and rain. Your hands were usually numb and stinging.

We who were guarding the barracks bags were picked up by a 2-1/2 ton truck and rode on top of the barracks bags until we rejoined Company K.

The 3rd Army drive to the Rhine River was bogged down in mud and impassable roads. We were supplied by parachute, supplies were dropped in fields. We settled into occupied houses to clean weapons and equipment. One midday, seated in a circle on chairs, we smoked and cleaned. Donald McCabe, our Navajo soldier, casually lifted his M3 machine gun, aimed it out the window and was surprised when a round went off. The bullet passed under my nose so close I swear I could smell it. I looked at him. He said casually “Sorry about that.” McCabe was a great soldier to have at your side. He could get unruly with drink. Two days later, he did find drink and a loose horse. He mounted it bareback and tried to get it to trot in a circle. He kept falling off, getting back on and falling off. It was almost funny. Finally, he couldn’t remount anymore and just lay on his back.

After several days, we climbed on our trucks and headed east. We didn’t know the next objective until we climbed down on the heights and looked across the Moselle River at Coblenz.

The river crossing was uneventful for our battalion. Smoke was laid down, but there was no artillery fire. Outboard engines powered the small metal boats and we were ferried across.

A paved road ran alongside the river with a high stone wall on the right side. On the wall was painted a sign “See Germany and Die.” We proceeded in a long column, with stops and starts. Occasional gunfire could be heard ahead. We passed a group of German prisoners seated and quietly smoking. A single MP guarded them. Their war was over. They looked relieved.

The column came to a long halt. I decided to explore. Looking up the hill on our right, past terraced vineyards, I could see a stone house. I scaled the wall and started up the hill, looking to see what was ahead and holding up the column. I passed the vineyards and came on the stone house. Standing in the doorway were a middle-aged couple and their son, his arm in a sling. With gestures and some English, they told me a shell had struck above the front door and a fragment of stone had broken the son’s arm. I could see the damage above the door. They invited me in and brought out food. We were able to talk with words and gestures. Some words in English, some in German. I thanked them, gave them cigarettes and worked my way down the hill. The column hadn’t moved.

We eventually gained the outskirts of Coblenz. Our battalion met little resistance. The objective was the capture of Ft. Constantine. We looked at it from a nearby hill. It was surrounded by high stone walls. K Company moved down the hill in column below the high stone walls. Passing the fort without meeting enemy fire, we began to cross a field in front of a railroad embankment with a stone retaining wall. Suddenly we were fired on from the fort. A machine gun opened up. We raced for cover. I was last in the company file led by Lt. Booker. My job that day was to carry the spare battery for the SCR300 radio, which kept us in touch with battalion headquarters. Everyone ran forward to a group of houses across the open field, about 100 yards away.

I made a bad mistake. I ran back to a cluster of houses we had just passed. Gaining the first house with four walls but no roof, I realized I was alone. To rejoin the company, I would have to race across the open field carrying the battery, about the size of an automobile battery. I would be a shooting gallery target for the machine gunner in the fort. Then I heard voices in German from adjoining houses. I was stranded in enemy territory. I didn’t know what to do next. I looked across the railroad tracks at the station house opposite. K Company was moving around inside the station. No one saw me. Suddenly one of our men ran out and laid down on the tracks, a suicidal act. I wanted to yell at him, but didn’t know how close the Germans were. The machine gun from the fort began firing. Bullets ricocheted off the tracks. He never moved. I decided not to make a run for it; I would wait until dark.

I discovered I could squeeze under the front stoop. An opening on one side looked across the field. I was protected by brick walls on the other three sides. I had just enough room to sit with the battery and my carbine. Morning became afternoon. I had the overseas edition of Time magazine with me. I passed the day reading, interrupted by bouts of diarrhea. Everyone had it from stress and poor sanitation. Squatting and relieving, I was being pushed out the opening. Mid-afternoon, a drunken German soldier came rolling down the sidewalk in front of the railroad embankment, headed across the open field to surrender. He had a bag slung over his shoulder. Should I use him as a shield? If the fort was occupied by SS troops, would they shoot both of us? If Germans in the nearby building saw me, would they shoot? If GIs across the field saw us, would I be mistaken for a German? I decided to wait.

When darkness came, I crawled out, walked in front of the embankment wall across the field and through the underpass to look for K Company. I didn’t know the password and kept to the shadows. When I heard one of our patrols coming, I hid in a doorway until they were close. I called out “Halt!” They were startled, but didn’t shoot at an American voice. When I got the password, I felt more secure. After stopping several patrols, I found K Company headquarters.

Lt. Booker was not pleased. When he was not pleased, unpleasant things could happen to you. So it was. He pointed out I had endangered the company. If the SCR300 radio battery had failed, there would have been no communication with battalion headquarters. I was detailed to guide the cooks with our food from our point of departure that morning to our new location. In darkness, I retraced my path through the underpass, across the field past the walls of the fort, to the top of the hill where I found the cooks. Carrying the marmite cans with hot foot in them, we worked our way past the fort and through the city to K Company headquarters, then guided them back up the hill. I returned alone and before dawn guided the cooks down again with breakfast. We were never fired on. This time the cooks stayed with the company until their supply trucks came up. Later that day, Ft. Constantine surrendered.

One of my best memories was finding a toothbrush. I had lost mine about a week before. Settling into the bombed-out house, which we would occupy for several days, I found a German toothbrush on the floor. It had dark ersatz bristles and had probably been used to clean Wehrmacht boots and apply shoe polish. I had always managed to brush my teeth once a day, whether or not I washed my face and hands. Going without a toothbrush really bothered me. I set about boiling water in my canteen cup and cleaned my new toothbrush. I used it until the war was over.

Coblenz was now coming under our control. Enemy soldiers started surrendering to our patrols, rather than resisting. Some walked into our area voluntarily. They were searched in the street in front of company headquarters. There was soon a litter of paper and German marks. Then a store of champagne was discovered. The dealer was there, one of the few civilians we encountered. Being good American soldiers, we offered to buy his champagne with invasion currency, which looked like cigar coupons. “Nein – marks, marks,” he said. We looked at each other. “He wants German marks!” We ran back to the litter of marks on the street and returned with loads of currency. For the next few days, I had champagne at my ready disposal. My bed was next to a window without glass. None of the windows had glass. Under my bed, bottles of champagne were neatly stacked. When I awoke in the morning, I reached under the bed, extracted a bottle and tasted it. If it had turned and did not meet my standard, I tossed it out the window and got another.

John Kerr, another of our company headquarters personnel, and I were poking around abandoned buildings when we came on a cellar a foot deep in brandy. Someone had broken into large casks and allowed the brandy to flow out. It became our late afternoon ritual to scoop up half a pitcher and climb a fire escape on the remaining corner of a destroyed building. We pulled two chairs from the building and settled into them to enjoy the setting sun and sip brandy.

The good times ended in a few days. We loaded onto trucks and headed for Boppard to attempt a Rhine crossing.

Richard Manchester

K Company, 345th Infantry Regiment

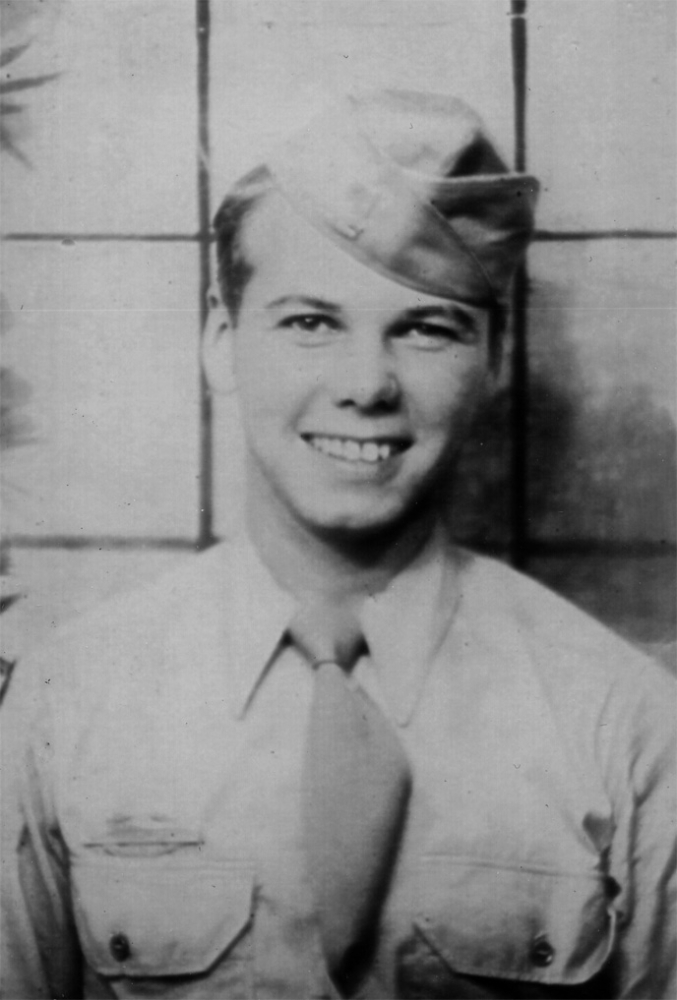

Dick was born August 5, 1925 in Baltimore. He attended schools in Philadelphia and Pittsburgh and graduated from Hollidaysburg (PA) High School in June 1943. He entered the Army in September 1943, enrolled in ASTP (Army Specialized Training Program). His basic training was at Fort Benning, GA. After six months at Clemson A&M (now Clemson University), he was assigned to K-345 of the 87th Division at Ft. Jackson, South Carolina. He emerged from overseas duty virtually unscathed.

After discharge from Indiantown Gap Military Reservation in January 1946, he attended Pennsylvania State College, graduating in 1950. He is in the process of retiring after 57 years in sales and marketing in the aluminum industry. Dick is married, and has six children (5 sons, 1 daughter); 6 grandchildren, and 2 great-grandchildren.