WWII Memoirs: Part 1 – The First Day of Combat

by Richard Manchester | 31 Dec 2010

I was a member of K Company – 345th Regiment. I was in the Communications Section of Company Headquarters, carrying the SCR536 Handy Talky, relaying and receiving messages to and from the platoon leaders or carrying the SCR300, communicating with Battalion Headquarters. What follows are my experiences during this time. It may be totally different from the experiences of other surviving members of my company. You are generally only aware of what is happening in a radius of 100 feet or so. Some incidents I can remember as part of a chain of events. Other incidents are isolated and I can’t put them in context. I will try to contribute more as time and memory permit.

THE FIRST DAY OF COMBAT

With full pack and rifle, we carefully went over the side of our cross-channel ship and worked our way down the cargo net to a landing craft (LCI) heaving alongside the hull in the long harbor swells of Le Havre. We were instructed to leap in the boat as it fell in the trough. With rifle and full pack added to our body weight, if we landed in the boat as it rose in the swell, you could break a leg. If you jumped or fell between the hull of the ship and the boat it could be fatal, of course.

We had left our barracks in Leek (England) on Thanksgiving Eve, been trucked to Southampton and ferried to Le Havre on the French coast. We waded ashore in the mid-day and pitched pup tents for shelter until trucks came to take us a short distance to our assembly area at St. Saen near Rouen on the Seine River. What followed were ten days of drizzling rain in an apple orchard, sheltered by pup tents, two men to a tent.

December 4, we climbed into French 40 and 8 boxcars (40 men or 8 horses) and began a frustrating journey through France to end ultimately in Metz to relieve a regiment of the 5th Division. Our train stopped, waited, back-tracked and after several days arrived in Metz in the late afternoon of December 8. The 5th Division had Ft. Driant, the last of several forts around Metz, surrounded. Before we could organize a full relief, the Germans in the fort surrendered.

What followed was out of control revelry by Company K as the men discovered Calvados, the potent French brandy. Soon the village streets were awash with rain and lurching drunken soldiers. One of the sergeants started to reprimand Pvt. Romero, who threw his rifle in the gutter and promptly urinated on it. Into the night it continued, until the Calvados ran out and the men passed out.

The following day, we were moved from the village to a former German Officers Candidate School outside Metz. The first evening, Tom McCabe, a Navajo, whom we later learned had to be kept from strong drink, brought in a skinned rabbit caught with his bare hands. We had roast rabbit for dinner.

On December 13, the 345th Regiment, including K Company, was headed for the Saar Basin to relieve a regiment of the 26th Division. The weather had been mild and rainy. It was going to turn colder. Our other two regiments, the 346th and 347th, were already engaged with the enemy, having relieved two regiments of the 26th Division a week earlier.

The landscape turned barren and hilly, broken with small patches of woods on the hilltops. We climbed out of our trucks 35 miles east and south of Metz, near the German border. We formed up behind a screen of woods in open formation. I noticed an overturned jeep and wondered idly if a jeep was more valuable to the Army than an infantryman. We passed through the small stand of woods and emerged on a bare ridge occupied by men of the 26th Division. They stood in their foxholes silently staring at us as we walked past. Near the end of the ridge was a foxhole. Next to it was an M1 rifle, stuck bayonet first in the ground with a helmet on top.

We started spilling off the ridge to walk down a long slope to a shallow valley. Suddenly the hillside erupted in shell bursts. We started running in surprise and panic. Tom McCabe had a shell explode in the angle between his outspread arm and leg as he threw himself to the ground. “Oh, Tom has been killed,” I thought, but he jumped up and ran on. As we gained the shallow valley, the shelling grew sporadic. Bob Polk, our supply Sgt. was lying down some 10 yards in front of me. He looked back at me with a silly grin and said, “I wish I had an ice cream cone.” Why was the supply sergeant in the attack? We began to dig our first serious foxholes.

Our men were formed up for an attack. They went up and out of the valley toward the enemy and a machine gun in a point of woods. Those of us in Company Headquarters remaining in the valley could hear firing and the ripping sound of a German machine gun. Then our men came streaming back, shouting “Tanks.” We stood stupefied, not knowing what to do. Panicked men ran past us. There was no one to stop the rout. Suddenly, Lt. Col. Leach appeared and started shouting orders at the men. Gradually, men stopped running and returned. Soon three of our Sherman tanks showed up and took position on the military crest of the hill facing the enemy. If there was a German counter-attack, it stopped. I was not scared; I was traumatized. I had a brief wild thought: “If General Eisenhower knew I was here, he would want me to be rescued.” The first day of combat is not as you imagine it from training films, lectures and field exercises. You could be killed. Survival is so often by chance. You can dig in, seek cover, hit the ground – but it’s all by chance.

Afternoon became evening. The night was cold. Stress brought thirst. My canteen was empty. There was no water. We were told not to leave our foxholes. Movement could be mistaken for an enemy patrol infiltrating our line. Ahead, out in the darkness, a soldier was crying “Mother.” No one was allowed to go to him. Sometime during the night, he stopped.

After that first day, our battalion went into regimental reserve and remained in reserve until December 23, when the 87th Division was pulled out of the line and began moving north to join the Battle of the Bulge.

In the intervening days, we took little shell fire, but stayed near our foxholes. The day after our initial attack, a German ME109 plane flew over our lines to observe our positions. Anti-aircraft machine guns opened all along our front. Before the pilot could escape, smoke trailed from his engine. He went down in a shallow dive behind our line beyond a hill. Next day an American P-51 plane flying overhead had to take evasive action to escape our gunners who mistakenly fired away. One day standing outside my foxhole, I heard a swishing sound above and behind me. Before I could move, an ejected spent aircraft fuel tank tumbled over my head to strike the ground about 10 yards away.

By now, L-4 Taylor Cub artillery spotter planes called Grasshoppers were in the air. In good weather, they did much to suppress enemy artillery fire.

My friend Dick Steck was selected to attend flamethrower school. This was a notice that we were going to attack the pillboxes in the Siegfried Line. Before that could happen, we were ordered to mount trucks. We were on our way for a long, cold drive on big flatbed trucks with canvas covers to Reims. We would be one of three new divisions to form SHAEF Reserve in case the advancing Germans broke through and aimed to take Paris.

Richard Manchester

K Company, 345th Infantry Regiment

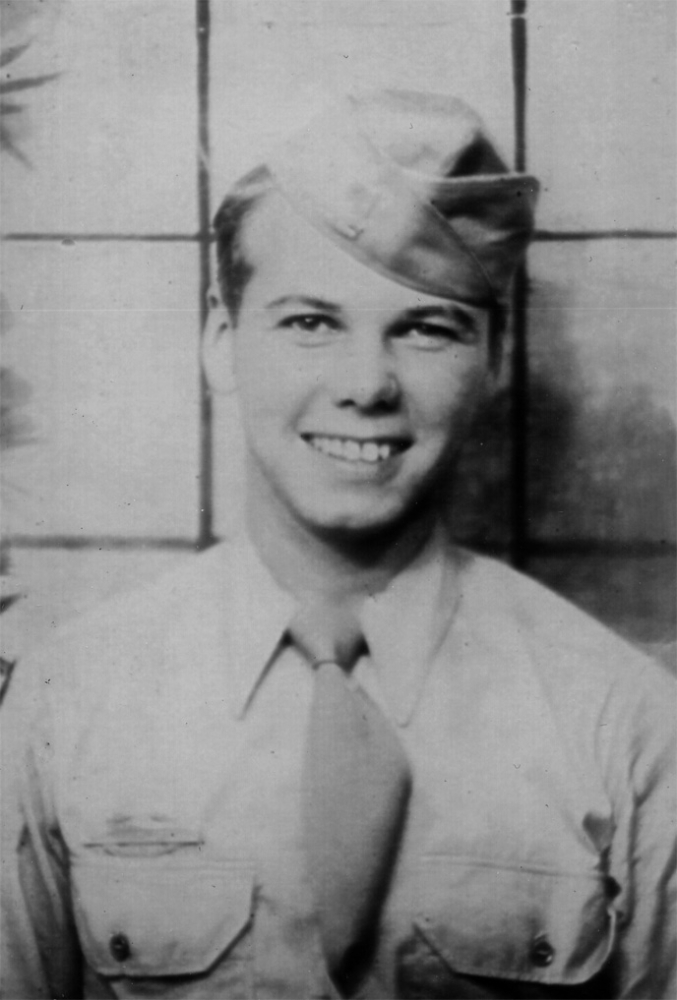

Dick was born August 5, 1925 in Baltimore. He attended schools in Philadelphia and Pittsburgh and graduated from Hollidaysburg (PA) High School in June 1943. He entered the Army in September 1943, enrolled in ASTP (Army Specialized Training Program). His basic training was at Fort Benning, GA. After six months at Clemson A&M (now Clemson University), he was assigned to K-345 of the 87th Division at Ft. Jackson, South Carolina. He emerged from overseas duty virtually unscathed.

After discharge from Indiantown Gap Military Reservation in January 1946, he attended Pennsylvania State College, graduating in 1950. He is in the process of retiring after 57 years in sales and marketing in the aluminum industry. Dick is married, and has six children (5 sons, 1 daughter); 6 grandchildren, and 2 great-grandchildren.